Introduction

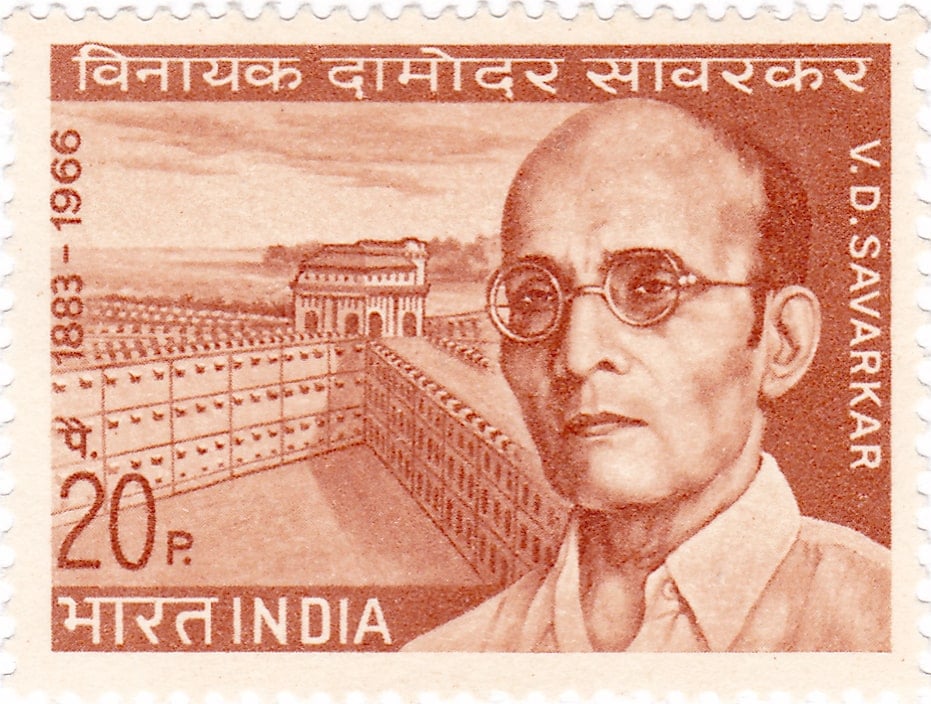

In this article, we are going to talk about the brave Indian nationalist that is Veer Damodarrao Savarkar. Veer Damodarrao Savarkar was a freedom fighter.

Because there has been a very positive aspect of his image in relation to the inner freedom struggle and there have been many negative aspects as well. Actually, he was not associated with the Indian National Congress for a longer time.

So if he was not associated with the INC, therefore, he was not too much in support for Savarkarji. So that’s why, as a freedom warrior, his contribution to the end and freedom of struggle has not been too much popularized.

Veer Damodar Savarkar- Birth, Family Background

He was born in 1883, in the Bhagur village of Nasik, Bombay presidency in that time, British India, and in the present day Maharashtra. His father’s name was the Damodarpant, his mother was Radhabai.

He was born in a Marathi Chitpawan Bramhin Hindu family. He had two brothers, Ganesh and Narayan, and also his sister’s name was Nainabai. So he was educated at the local Shivaji High School.

Childhood Incident

Reason Behind Suffix Veer before His Name

At the age of around 12, a group of Muslims attacked on his village. His village was mainly a Brahmin village. So obviously the number of people in the villages was less and the attacker swapper a bit more.

But still, he defended very vigorously his village and you know, he led the masters of the village at such a small age and he fought bravely. So that is why, since then, he was given the name as “Veer”.

Education of Vinayak Damodarrao Savarkar

He enrolled himself into Ferguson College, Pune. In the year 1902 and there he involved himself in the Indian nationalist party. There, he was being expelled from the college for his activities.

(Reason: Ferguson college was government financed college, in a government financed college, he was doing nationalist activities. So they expelled him from college).

Later, after some time, college allow to complete his BA degree in college.

Savarkar went to London for further study

Shyamaji Krishna Verma sent him to London on Scholarship

Shyamaji Krishna Verma had to obtain a scholarship to law at the Lord the Grains College in London. So, after completion of his BA degree, he was being held by Shyamaji Krishna Verma to go to London to study law at Grains College. There in London, he stayed at a place named as India House.

India house was a place where many Indians were living and it was basically a thriving Center for Student political activities. This India house was also organized by Pandit Shyamaji Krishna Verma. So, there Veer Damodarro Savarkar got a platform to propagate his ideas.

In India, he was already bit famous because of his activities. There also he continued his activities. So a he founded the Free India society.

The Free India society was it was to organize fellow Indian students in England, with the goal of fighting for complete independence through a revolution. He said that only after raising a revolution they will get complete independence.

Swadeshi movement

At the age of 15, he organized a youth organization to advocate the nationalist ideas. And the same time when he was pursuing his BA degree from for Ferguson college.

He was very much inspired by the Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak announcement to boycott the British course. Obviously, he was he enrolled in 1902, and in Ferguson college and obviously 1905, Swadeshi movement was at its peak, therefore he was very much inspired by the Swadeshi movement.

Ideology of the Veer Damodarro Savarkar

“We should halt grousing about this English Officer or that officer, this rule or that rule. There would be no cease to that, our movement must not be finite to being opposite to any specific law. But, it must be for gaining the power to make rule itself. In short, we want complete freedom. “

Meaning: He says that why are you saying that the British officer is doing bad, and that the British officer is doing that? Why are you saying that this law is bad, and this law is that?

Our focus, the Savarkarji said that our focus is to have the authority to make love ourselves. And that can only be obtained if you have complete independence.

He said that we will get complete independence through our revolution. And obviously, these ideas were too much revolutionary at that point of time. And obviously, they will not be liked by the British administration.