Hello friends, I am back again with new interesting biography of Sher Shah Suri. In the brief reign of five years, there were so many changes happened in India. That is the reason his period was important to understand Indian History.

Introduction

Sher Shah Suri was one of the most prominent Muslim rulers in India. He was an ethnic Afghan ruler, who came into power in 1540 CE. Later Mughal Emperors widely followed his principles. When he died suddenly in 1545, his son Islam Shah became his successor.

Although his reign was for a short span of five years, Sher Shah Suri had brought about a drastic change in the way Mughal rulers functioned. His principles and ethics were followed by many Mughal rulers who came after him, although they were traditionally his nemeses.

Significance Of Sher Shah Suri in Indian History

Born as Farid Khan, Sher Shah Suri was the founding father of the Sur Empire, which lasted for about 16 years (1540 and 1556 CE) in India and its capital was in Sasaram, which is modern-day Bihar. He is famous for many things and his skill set is more than many of the contemporary rulers of his time.

Although he took over the reins of his destiny and became the founder of the Sur dynasty, his road to success was a rocky one. First, he worked under many ministers to attain the position of a commander within the Mughal army headed by Babur. Later, he became the governor of Bihar.

In 1537, when the son of Babur, Humayun was on an expedition, Sher Shah took advantage of his absence and annexed the state of Bengal. Sher Shah established the Sur dynasty in Bengal but continued working in conjunction with the Delhi Sultanate.

He was an excellent strategist, a smart administrator and a competent general. Sher Shah started reorganizing his workforce and functions in the empire.

He brought about new rules and regulations, which benefited everyone. His policies and work ethics were so powerful that the Mughal emperors who came after him, mostly Akbar, followed them.

He ruled for a period of five years, from 1540 CE to 1545 CE. He introduced the new currency of the rupee. The primary Rupiya that he issued to replace the earlier used currency with ‘Tanka’. He made many beneficial changes in the economic and military sectors and arranged the postal system.

Although he fought against the Mughals for power, the Mughal emperors well-appreciated his strategies and contributions. Out of them, Akbar was a great fan of the administrative policies of Sher Shah Suri.

Apart from changing the administrative and economic sectors, Suri also redeveloped many failing cities. One of them was Dina-panah city of Humayun, which he renamed Shergarh. He also revived the historical city of Pataliputra, modern-day Patna, which had not fallen apart since the 7th century CE.

One of his biggest achievements is the construction and extension of the Grand highroad from Chittagong, which is in the province of Bengal, to Kabul in Afghanistan, which is on the far northwest side of the country.

He made so many rules against robbers and bandits that many of them shuddered to steal from common citizens. He built caravansaries at several intervals on the Grand Trunk road, offering relief to travelers.

His policies, innovations and reforms were so drafted and executed that even his arch-rival, Humayun, was in awe of him. He called him ‘Ustad-I-Badshahan’, teacher of kings. The most astonishing thing about him was during his reign, he never lost a battle.

History of Childhood And Early age

Family History of Sher Khan Suri

Sher Shah Suri was named Farid Khan at the time of his birth. There is an interesting story behind how he came to be known as Sher Singh. It happened later when he was a youngster at the court of Jamal Khan.

His grandfather, Ibrahim Khan Sur, was a horse trader. Later, he became a landlord in Narnaul, present-day Haryana, and represented his patron, Jamal Khan Lodi Sarangkhani. Ibrahim Khan Sur was assigned a few villages in Hissar.

After Sarangkhani was appointed as the governor of Jaunpur by Sikandar Lodi for supporting him in gaining the throne, he became hopeful for a brighter future. The Son of Jamal, Khan-i-Azam Ahmad Khan Sarangkhani, was his successor as he had a rank of 20,000 sawars (A system of ranking according to the Mughal and Maratha periods).

Sarangkhani also appointed Ibrahim Sur’s son Hasan to the position of iqta (Islamic practice of tax farming) of Sasaram and Khawaspur-Thanda with a rank of 500 sawars.

In 1580, the famous historian Abbas Khan Sarwani of the Mughal empire wrote a memoir about Sher Shah. In that, he notes down many interesting facts about his life.

According to him, Sher Shah’s grandfather came from the family of the Sur, who are believed to be the descendants of Muhammad Suri, one of the princes of the house of the Ghorian. He left his native country and married an Afghan chief’s daughter.

Ibrahim Khan Sur came to Hindustan with his son Hasan Khan from Afghanistan. His native place was called ‘Shargari’, according to the Afghan language, and ‘Rohri’ according to the Multan language. It is in the Sulaiman Mountains on the banks of the Gomal River. They worked for the landlords, Muhabbat Khan Sur and Daud Sahu-khail.

Although Ibrahim Khan Sur began as a trader, he eventually became a landlord in the Narnaul area. He represented his patron, Jamal Khan Lodi Sarangkhani, and was assigned a couple of villages in the Hissar district. The Mazar of Sher Shah’s grandfather still exists in Narnaul.

Although the exact place and date of birth of Farid is a mystery, many historians believe he was born during the reign of Bahlol Lodi. He was the first child amongst the eight sons that Hassan Khan had from his four wives. However, due to his bad relationship with his father, Farid left his hometown and went to Jaunpur, for further studies.

Rocky Relationship of Sher Shah with his Father

Omar Khan Sarwani, an ethnic Pashtun historian, notes down many interesting excerpts about Sher Shah Suri’s life. According to him, Farid has been looking after Fargana in Delhi, which is present-day Bhojpur, Buxar, Bhabhua in Bihar, since a very young age.

Being a counselor and a courtier of Bahlul Khan Lodi, Omar Khan has also made interesting observations about Sher Shah. He further notes that Farid Khan did not get along well with his father as he was neglected by him in favor of his younger brothers by his fourth wife.

During his days as a rebel, Farid ran away from his home and took refuge at the home of Jamal Khan, the governor of Jaunpur in Uttar Pradesh. However, when his father realized that his firstborn was missing, he wrote a detailed letter to Jamal Khan.

In the letter, he informs Farid Khan about the misunderstanding between him and his son. He further tells him that the matter between them was not grave and did not warrant such an overzealous response.

He asks Jamal Khan to speak with Farid and send him back. However, if he refuses, he asks Jamal Khan to keep him and give him the required religious training to be a better man and ruler.

Although Jamal Khan tried to convince Farid to return home, Farid refused to budge. In his letter, Farid assures his father about the learned men in the city of Jaunpur and asks him not to worry about his education as he was planning on not returning.

Belonging to the Pashtun Sur tribe, Sher Shah was related to Babur’s brother-in-law, Mir Shah Jamal. Despite the rivalry between Humayun and Sher Shah became a subject of much interest in history, Mir Shah Jamal remained loyal to Sher Shah.

The most fascinating aspect of Sher Shah’s journey is when the title of ‘Sher’ was conferred upon him. As a young man, he displayed exemplary feats of courage that awed his contemporaries and his masters.

One of them was to save the life of the king of Bihar, where he single-handedly killed a tiger that suddenly appeared from nowhere. Thereafter, his exemplary journey began.

Battles Fought By Sher Shah Suri

Sher Khan fought and won many battles during his short reign. Although he only ruled for a few years, he brought about immense change in his kingdom. People respected and revered him as an able ruler. However, before he assumed power, he had to fight and win many battles.

Annexation of Bihar and Bengal

Farid Khan was directly working under Bahar Khan Lohani, the Mughal Governor of Bihar. Due to his courageous personality, Bahar Khan conferred the title of Sher Khan to Farid. When Bahar Khan passed away, Sher Khan took over the reins as the next heir to the throne, Sultan Jalal Khan, was still a minor.

However, Sher Shah was an excellent strategist, and he used his newfound position to expand his rule in different parts of Bihar. When Jalal realized what was happening, he tried to stop Sher Shah from taking over. He reached out to Ghiyasuddin Mahmud Shah, the Sultan of Bengal and asked him for help.

In response, Ghiyasuddin sent an army to defeat Sher Shah. However, his army was crushed by Sher Shah at the battle of Surajgarh in 1534. Victorious, Sher Shah allied with the Ujjainiya Rajputs and other local rulers to gain control of Bihar.

However, this was one of the many battles he fought and won in the North. In 1538, Sher Khan defeated Mahmud Shah but was unable to conquer Bengal because of Humayun’s military interference.

In 1539, Sher Khan fights against Humayun at the Battle of Chausa, which he wins. Later, he defeats Humayun at Kannauj in 1540. Hence, he assumes power in Bengal and Bihar.

Sher Shah Conquers Malwa

Sher Shah now turns his attention to the North-Western states of Malwa and Mewar. But before he could proclaim his power in those states, many changes occurred on the political front between the years 1537 CE and 1542 CE.

In 1537, Qadir Shah becomes the new ruler of the Malwa Sultanate after the death of Bahadur Shah of Gujarat. Thereafter, he seeks the support of the powerful rulers of the Khilji rule of Malwa.

Bhupat Rai accepts Qadir Shah’s service under the regime of Malwa. However, in 1540, Bhupat Rai passes away, leaving Puran Mal to be the most powerful man in the Eastern Malwa region.

In 1542, Sher Shah easily conquers Malwa as Qadir Shah turns out to be a weak opponent who flees for his life. Shuja’at Khan, the newly appointed governor of Malwa reorganized the administrative structure of Malwa and tried to bring about positive changes.

Sher Shah brought about a massive change in his rule by turning his attention towards the Western regions. Aware of the power held by Puran Mal, Sher Shah ordered him to appear before him.

Puran Mal easily acceded his power left his brother Chaturbhuj under Sher Shah’s patronage. Thus, after making an alliance with Puran Mal, Sher Shah effectively extended his rule to Malwa.

Trouble in Malwa

After Sher Shah had formed an alliance with Puran Mal and promised to keep him safe, an unfortunate incident forces him to break his promise.

Many Muslim women of Chanderi, who were under the rule of Sher Shah, requested an audience with Sher Shah. They share troubling news with him and accuse Puran Mal of committing heinous acts towards their husbands and daughters.

After listening to them, Sher Shah faces a predicament. On the one hand, he had promised to save Puran Mal. On the other hand, he knew he must avenge the women who were targeted by Puran Mal’s evil designs.

Sher Shah consults his ministers and ulama to come to a solution. However, when the ulama issues a fatwa against Puran Mal and punishes him to death, Sher Shah complies with their decision. Sher Shah sends his troops to attack Puran Mal’s camp.

When Puran Mal sees them, he immediately kills his wife and asks other Rajputs clan leaders to end their kin as well. Although accounts by historians of the number of Rajputs present at camp of Puran Mal differs, they agree that numerous notable Rajputs were annihilated that day.

According to historian Abbas Sarwani, the situation gets worse when the Rajput families start committing Jauhar. At the gates of death, Hindu men go on a rampage, killing their women and children and even themselves.

On the other hand, a military of Afghans circles them on all sides to kill them. Within minutes, the entire population of Rajput clans disappears into nothingness.

In this incident, a few women and youngsters survived. Puran Mal’s daughter was sent to become a dancing girl for minstrels. On the other hand, his nephews were castrated and tortured. To explain his actions, Sher Shah claimed it was an act of revenge for enslaving Muslim women.

Annexation of Marwar

In 1543, Sher Shah Suri turns his attention towards Marwar. He brings an enormous army of 80,000 men to fight the Rajput king, Maldeo Rathore. Maldeo Rathore has an army of 50,000 cavalries who are no match for Sher Shah’s soldiers. However, Sher Shah uses a different strategy to tackle the Marwar king.

He marches towards the village of Sammel within Jaitaran, which is 90 kilometers east of Jodhpur. After a month of constant fights, Sher Shah bears the brunt of food shortages, injuries and other difficulties of having a large army. However, being a gifted strategist, Sher Shah uses a devious ploy.

He decided to create differences between Maldeo Rathore and his generals to break them from within. He used forged letters that mentioned incorrect information about his trusted commanders bearing allegiance with Sher Shah.

These letters were intercepted by men of Maldeo. Believing this to be true, Maldeo abandoned his commanders and left them to deal with Sher Shah’s army.

After Maldeo left for Jodhpur, his generals Jaita and Kumpa were forced to fight with barely a few thousand men against a league of 80,000 cavalries and cannons. This came to be known as the battle of Sammel.

Eventually, the war ended with Sher Shah as the victor. However, he lost several men and faced severe losses. He realized later that even after winning, the losses he incurred were far deeper than the award.

Thereafter, general of Sher Shah Khawas Khan Marwat started governing Jodhpur and looked after the territory of Marwar from Ajmer to Mount Abu in 1544.

The Administrative Policies of Sher Shah

Sher Shah brought about a drastic change in the implementation of currency, the system of tri-metalism that became the base of the Mughal coinage. While the term rupya was used for any silver coin, Sher Shah gave a very specific role to the term rupee. A silver coin that weighed 178 grains became the precursor of the present-day rupee.

Today, the rupee is the national currency of many South-East Asian and Asian countries, like Indonesia, Mauritius, Nepal, Seychelles and Sri Lanka and other countries as well.

Apart from the rupee, two other coins were introduced in the tri-metallism system. Gold coins called mohur that weigh about 169 grains and copper coins called paisa were also a part of the new coinage.

According to numismatists Goron and Goenka, the coins belonging to 1538 CE, state that Sher Khan assumed the royal title of Farid al-Din Sher Shah. Also, these coins were minted even before the battle of Chausa.

One of the biggest achievements of Sher Shah was his efforts to rebuild the Grand Trunk road. During his tenure, he rebuilt the enormous road and modernized the extensive road that runs from modern-day Bangladesh to Afghanistan.

Caravansaries, or lodging inns and mosques, were built on each side of the road to supply relief to travelers. He also planted trees and dug wells. Apart from that, he also established an efficient postal system where mail would be carried by horse riders.

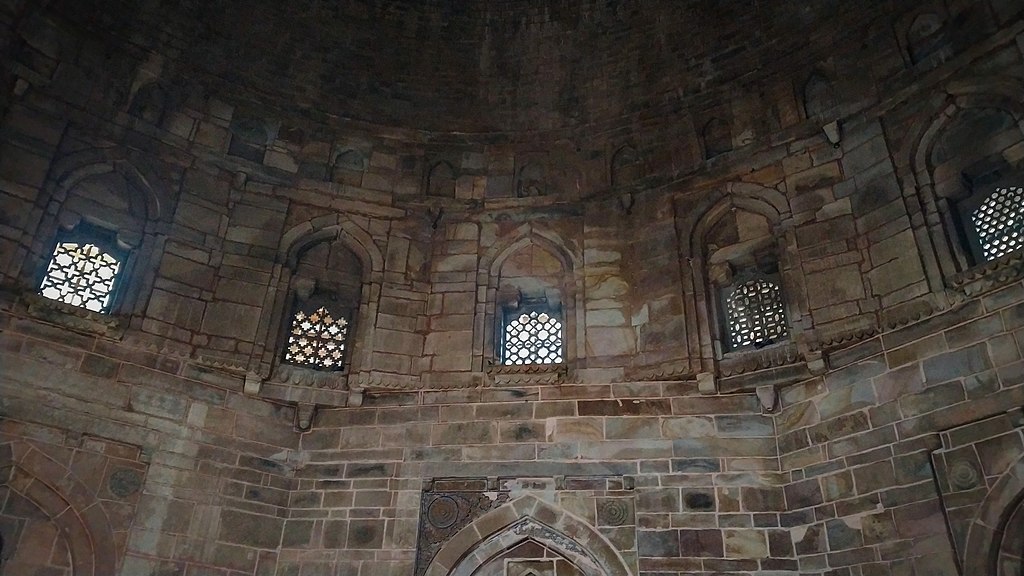

Sher Shah also built many monuments, such as Rohtas Fort, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, several structures within the Rohtasgarh Fort in Bihar, the Sher Shah Suri Masjid in Patna, the Qila-i-Kuhna mosque inside the Purana Qila complex in Delhi, and the Sher Mandal, an octagonal building also inside the Purana Qila complex. He rebuilt the city of Bhera in 1545 and a grand mosque within it.

Although Sher Shah was tolerant of Hindus, the massacre and surrender of Raisen was an exception. The memoir called Tarikh-i-Sher Shahi, written in 1580 CE by historian Abbas Khan Sarwani belonging to the court of Mughal ruler Akbar, provides a detailed account of Sher Shah’s administration.

Death and Succession of Sher Shah Suri

The Chandela and Baghela Rajputs of Mahoba Baghelkhand were not ready to accept Sur empire’s authority. So, Sher Shah decided to conquer their lands. He began work on the siege of Kalinjar in 1543. However, he unexpectedly died during the siege.

To enter the fort, Sher Shah used several war tactics. However, all of them failed. Eventually, he ordered the walls of the fort to be blown up with gunpowder. But the effects of that were extremely harsh. The Rajput garrison of the fort attacked Sher Shah’s army at night. He became seriously wounded as a result of the explosion of the mine, and eventually he died.

After his death, he was succeeded by his son, Jalal Khan, who continued the siege and slaughtered the entire Rajput garrison of Kalinjar fort. He was titled Islam Shah Suri. His mausoleum, the Sher Shah Suri Tomb, stands in the middle of a man-made lake at Sasaram, a town on the Grand Highroad.

Interminable Legacy of Sher Shah Suri

Although Sher Shah has many feathers on his cap, several experts have made many uninspiring observations about him as well. Historians such as Abd al-Qadir Bada’uni accuse Sher Shah Suri of destroying old cities and rebuilding them for his benefit.

Shergarh is one of the prime examples. It was once a thriving town where Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism flourished peacefully. The inscriptions found in the area state the facts.

Sher Shah is also accused of destroying Dinpanah, one of the six cities in Delhi that Humayun was constructing. After Sher Shah rebuilt the city, it was destroyed and re-conquered again by Humayun in 1555.

Tarikh-i-Da’udi also states that Sher Shah destroyed Siri. Abbas Sarwani states that he had the old city of Delhi destroyed. Tarikh-i-Khan Jahan states that Salim Shah Suri had built a wall around Humayun’s imperial city.

Although historians have both stated positive and negative outlooks towards Sher Shah’s reign, all of them agree he was an excellent ruler. In a short span, he has made so many unrivalled achievements.

His policies on controlling the administration and making rules to benefit his people inspired the Mughal rulers who came to power after his demise. Sher Shah Suri has undoubtedly left an indelible mark on his history.

Citations

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sur_Empire

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sowar

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sher_Shah_Suri

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sher-Shah-of-Sur

https://byjus.com/free-ias-prep/sur-dynasty-1540-1555/

Featured Image Credits: Ustad Abdul Ghafur Breshna